They used to be called “natural philosophers” before William Whewell coined the term “scientist” in 1833. During the Victorian boom, it appeared that scientists could work on their own, applying their scientific method to all kinds of natural phenomena, and make great progress independently of philosophy. The two factions grew apart, with scientists sucking all the prestige out of the room with their experiments in everything from atomic physics to cosmology, leading to highly visible advances in things that make a difference in human life: transportation, energy, and health. One might call the 20th century a “philosopher of the gaps” period, with scientists basking in the headlines and philosophy finding less and less to do.

That’s a distorted picture, of course. Some of the greatest philosophers of science in history (e.g., Popper, Kuhn) made big waves in the 20th century and continue to do so (think of Thomas Nagel). And as philosophers like to point out, philosophy is unavoidable: ignoring philosophy is a philosophy in and of itself. In terms of social prestige, though, philosophy has descended far from its lofty position as “queen of the sciences” (other contenders for that title being astronomy and mathematics). The big grant money flows to the science buildings, with philosophers across campus still (in the popular misconception) meditating on their navels. Some philosophers figure the best way to get some of their prestige back is to advertise their benefits for scientists.

Between Science and Philosophy

Now a group of philosophers, including Elliott Sober, have made their plea in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences under the title, “Why Science Needs Philosophy.” Nature summarizes their appeal:

Nine philosophers and scientists come together to argue for a rapprochement for their disciplines. They offer three examples in stem-cell, microbiome and cognitive science to show how philosophy can boost understanding and clarify scientific thought — and they offer a host of suggestions for how to make it happen. [Emphasis added.]

ID advocates should be interested in those two things: boosting understanding and clarifying scientific thought. Let’s look at the philosophers’ points with a view to contributing to the rapprochement. First, they quote Einstein:

A knowledge of the historic and philosophical background gives that kind of independence from prejudices of his generation from which most scientists are suffering. This independence created by philosophical insight is — in my opinion — the mark of distinction between a mere artisan or specialist and a real seeker after truth.

Now that they have scientists’ attention, they explain their objective:

Despite the tight historical links between science and philosophy, present-day scientists often perceive philosophy as completely different from, and even antagonistic to, science. We argue here that, to the contrary, philosophy can have an important and productive impact on science.

The specific instances they discuss (stem cells, the microbiome, and cognitive neuroscience) could be substituted with many others. Of more applicability to ID’s interests are the principles they say give philosophy value in science. Here are the basic principles with a view to how intelligent design already contributes value, and could advertise that value better.

Conceptual Clarification

Scientific terms need clarity, lest scientists and the public talk past each other. Dunne’s Law quips, “The territory behind rhetoric is too often mined with equivocation.” If scientists desire objectivity over rhetoric, they must not only define their terms unequivocally, but also clarify the concepts behind the terms.

The authors use the word “stemness” as an example of a concept needing clarity. That’s not the only occasion where “philosophical analysis highlights important semantic and conceptual problems” in terminology.

Conceptual clarifications not only improve the precision and utility of scientific terms but also lead to novel experimental investigations because the choice of a given conceptual framework strongly constrains how experiments are conceived.

Notice the emphasis on mental activity (“are conceived”) and moral value (“precision”) in the statement. Can materialists even employ mind as a valid concept? Can they value precision as a good thing to strive for, when their only tool is natural selection?

ID scientists who have debated more conventional scientists know well the need for conceptual clarification. They have dodged the land mines of straw-man tactics (“ID is just creationism in a cheap tuxedo”), bandwagon appeals (“all scientists agree”), or personal attacks (“you’re just motivated by your religion”). Philip Johnson gave exceptional clarity to the issue, showing that evolution (a highly equivocal word itself), as Darwinists use it today, relies on unguided natural processes, regardless of the mechanism du jour. By standing outside the current consensus, ID can more objectively critique the definitions of terms and concepts used by Darwinians (evolution, selection, methodological naturalism, etc.) and insist on clarity up front. Otherwise, any debate is like trying to hold a conversation on two different radio channels.

Critiquing Assumptions

The authors give another example where scientists can benefit from the philosophy department:

Complementary to its role in conceptual clarification, philosophy can contribute to the critique of scientific assumptions — and can even be proactive in formulating novel, testable, and predictive theories that help set new paths for empirical research.

The examples they use to illustrate this (the immune system and symbiotic communities), have led to practical experimental approaches. ID certainly is aware of assumptions underlying Darwinian evolution (e.g., philosophical naturalism, an amoral universe, man as mere animal), and spends time debunking them. How can ID also be more proactive in setting new paths for empirical research? It’s already happening, as shown in Discovery Institute’s Summer Seminars that inspire young scientists to explore research along ID lines: e.g., life as information-based, programming as an indicator of mental activity, aesthetics as a sign of intentional action. The burgeoning field of biomimetics has shown immense practical value under the assumption that good design will be found in biological systems. How much more with the hypothesis they were purposely designed rather than cobbled together by happenstance? Behe’s new book Darwin Devolves might inspire medical science to identify and restore broken systems that cause disease.

Critiquing bad assumptions and becoming proactive in setting research pathways with better assumptions are two sides of the same coin. Perhaps showing more of the shiny side (proactive approaches in empirical science) will attract more young researchers to the ID camp by showing them ways they can actually use design assumptions in their experiments.

Overcoming False Beliefs

In another subsection, the philosophy advocates endorse two atheist philosophers who they feel have advanced scientific research. The first is the late Jerry Fodor. Some ID advocates might disagree with Fodor’s modular conception for human consciousness, with its evolutionary overtones, as an assumption that sent cognitive neuroscience in a wrong direction. The point is that philosophy can steer science by challenging paradigms. Fodor actually helped ID in a back-handed way by debunking natural selection, as Michael Egnor pointed out here. The other atheist is Daniel Dennett, whom the philosophers feel advanced the “theory of mind” by analyzing the source of false beliefs. How far can such a theory go, though, when the advocate believes mind is a manifestation of molecules? As Philip Johnson and Nancy Pearcey have pointed out, materialists often fail to point their baloney detectors at their own beliefs.

The above examples are far from the only ones: in the life sciences, philosophical reflection has played an important role in issues as diverse as evolutionary altruism, debate over units of selection, the construction of a “tree of life”, the predominance of microbes in the biosphere, the definition of the gene, and the critical examination of the concept of innateness.

The problem with these examples is that they are all coming from within the evolutionary paradigm. ID has the advantage of stepping outside the paradigm and applying philosophy’s valuable inputs from a fresh perspective: clarifying concepts, critiquing assumptions, and overcoming false beliefs.

Inspired by these examples and many others, we see philosophy and science as located on a continuum. Philosophy and science share the tools of logic, conceptual analysis, and rigorous argumentation. Yet philosophers can operate these tools with degrees of thoroughness, freedom, and theoretical abstraction that practicing researchers often cannot afford in their daily activities. Philosophers with the relevant scientific knowledge can then contribute significantly to the advancement of science at all levels of the scientific enterprise from theory to experiment as the above examples show.

For the rest of their essay, the authors provide suggestions for bringing science and philosophy back together for the benefit of both. If philosophy within the evolutionary paradigm can accomplish these things, how much more can ID do it better with its broader perspective? You can’t see the fog from within it as well as you can from outside it. ID is better positioned to see which way the wind is blowing the fog.

Instead of moving with the fog when it is falling over a cliff, ID can blow the fog upwards and away, providing clarity for science to see the best way forward. Why? Because ID, both as philosophy and science, believes that mind, information, and design are not phantom products of aimless processes, but real, useful concepts — realities that humans should employ for understanding and for mutual benefit.

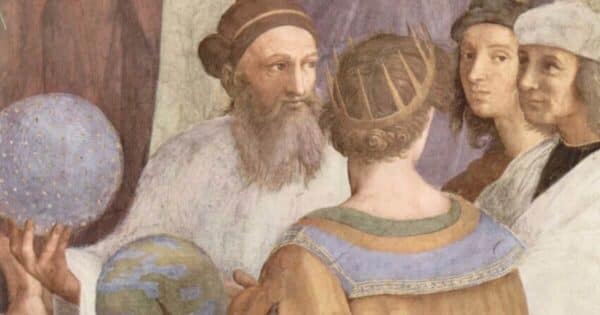

Image: Detail from The School of Athens, by Raphael [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons.